Peer Reviewed Studies on the Association of Income With Obesity and Physical Fitness

How Our Surroundings Tin Assist or Hinder Active Lifestyles

Whether it's biking to work or taking the stairs, walking the dog or parking farther abroad from the store, being physically agile offers countless benefits. Research shows that regular exercise makes people bacteria, stronger, smarter, and healthier. And so why aren't more people making physical activity a daily addiction? Myriad reasons keep many people off their feet, but the and then-called "built environment" our man-made globe, with its cities and neighborhoods, streets and buildings, parks and paths-plays a major role. Our social surroundings thing, too: Supportive families and coworkers, for example, may make it easier for people to go upwards and get moving. Where we live, learn, work, and play appears to accept a neat deal to do with how agile we are. (1–6)

This commodity briefly reviews research on how various settings influence our activeness levels, the policies that shape them, and their roles in perpetuating disparities in obesity rates.

Physical Activity Environs Research by Setting

Families

Family unit can exist the seedbed for a physically active life. (seven,8) Studies bear witness that parents are especially of import as models, encouragers, and facilitators of concrete activity in children and adolescents. Their roles include everything from ownership sports equipment and taking kids to practice to paying fees and doling out praise. (ix,10) Other important factors in raising agile children include paternal activity levels and positive reinforcement, maternal participation, sibling involvement, fourth dimension spent outdoors, and family unit income. (8,10)

What are the all-time ways to reach out to parents and in turn, get kids moving? Most family-based programs studied to date have had only express success in increasing children's activity levels. (11,12) But programs that accept place in the dwelling bear witness some hope, as practise programs that include confront-to-face meetings or phone calls with parents.

Worksites and Agile Commuting to Piece of work

At the aforementioned time, worksites are ideal settings to exam concrete action programs-controlled environments with easy admission to employees through existing channels of advice and back up networks. Employers can brand stairwells more attractive, safer, and easier to employ than elevators, and can put signs by elevators encouraging employees to take the stairs. (17–19) They tin can build onsite gyms, adopt policies that encourage exercise breaks during the workday, compensate employees for joining gyms, or offering health insurance incentives for physical activity. (14,twenty)

The U.S. Task Force on Community Preventive Services has found that worksite nutrition and physical activity programs can accomplish modest improvements in employee weight; few of those studies, all the same, changed the work environment to make it easier to be agile. (21) Worksite programs that aim to integrate short bouts of action into the workday routine, through practice breaks, pedometers, and like efforts, also show promise for increasing activity. (22)

The built environment is a decisive factor in how people get to piece of work. Sidewalks and protected cycle lanes, or the availability of bike storage, may make it easier for people to take active commutes; similarly, access to public transportation may too increase physical action, since information technology gives people a adventure to walk to and from a train station or bus end. Lachapelle and Frank (23) constitute that Atlanta residents who had employer-sponsored transit passes were more likely to meet physical activity fourth dimension recommendations than those who did non. Another small report plant that employees who had bike storage in the workplace, too as cultural support for agile commuting, were more likely to walk or bike to piece of work. (24)

Schools and Active Commuting to Schoolhouse

Schools, like worksites, are platonic settings to test programs for boosting student fettle. Nearly all children and adolescents spend the meliorate part of their days in classes, and nearly sites already accept scheduled recess periods and sports facilities that tin can be used to make concrete activeness part of the schoolhouse 24-hour interval. (14) A recent Cochrane Review of 55 child obesity prevention studies institute that increasing physical activeness sessions and developing physical activity skills during the school week were among the promising strategies for obesity prevention. (25) Programs that combine nutrition and physical activity seem to exist more effective at reducing children's trunk weight than those that focus on concrete activity alone. (26)

Schools, like worksites, are platonic settings to test programs for boosting student fettle. Nearly all children and adolescents spend the meliorate part of their days in classes, and nearly sites already accept scheduled recess periods and sports facilities that tin can be used to make concrete activeness part of the schoolhouse 24-hour interval. (14) A recent Cochrane Review of 55 child obesity prevention studies institute that increasing physical activeness sessions and developing physical activity skills during the school week were among the promising strategies for obesity prevention. (25) Programs that combine nutrition and physical activity seem to exist more effective at reducing children's trunk weight than those that focus on concrete activity alone. (26)

Schools' sports facilities can too serve the community at large. A pilot written report found that opening an later on-hours supervised schoolyard increased the outdoor activity levels of inner-urban center children past 84 percent compared with a matched control community. (27)

Active travel to school has also received attending as an obesity prevention strategy: In 1969, near half of U.S. elementary and heart school children walked or biked to school; in 2009, however, only well-nigh xiii percent of uncomplicated and center school children did. (28) Some, merely not all, studies notice a link between active school commutes and healthy weight. (29) For example, a contempo nationally representative U.S. study found that youth who walk or bike to school tended to be leaner and log more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each solar day. (xxx) The written report, like many studies of active transport to school, (29) evaluated children at one point in time, all the same, so information technology can't tease out cause and effect.

Neighborhoods

Where we live affects how nosotros live. Sidewalks, protected bicycle lanes, street designs that slow traffic and make it safe to cross, parks, gyms, shops and other destinations inside walking distance-all of these neighborhood features can make a divergence in how active nosotros are. Research on exactly how neighborhood characteristics impact physical activity is growing. Just the field is notwithstanding in its early stages, with express data from long-term studies. (31) And so-called "self-choice bias" remains a concern: Do active people motility to neighborhoods with sidewalks and parks, or does living in a neighborhood with sidewalks and parks make it more likely that people volition be active? Besides, most studies have been carried out in the United states of america and other developed nations, then results may differ in rural areas and developing countries.

Access to physical activity facilities

Low-income and minority neighborhoods have fewer recreational facilities than wealthier and predominantly white communities, (32–34) a factor that may contribute to racial/indigenous and socioeconomic disparities in obesity rates. (4) I study, for example, looked at admission to recreation facilities in neighborhoods across Manhattan and the Bronx, greater Baltimore, and Forsyth County, Northward Carolina. It found that minority and low-income neighborhoods were three to eight times more likely to lack high-quality recreational facilities than predominantly white or wealthier neighborhoods. (33) There have been mixed findings, however, as to whether just living in neighborhoods with more recreation facilities actually leads to more than active lifestyles. (1,35) Information technology's possible that other factors, such as price, may be a bulwark to working out, fifty-fifty when people accept gyms nearby. (four)

Walkability and Sprawl

A number of studies have looked at whether living in a "walkable" neighborhood-one that has sidewalks, crosswalks, stores, and leisure destinations-has a positive effect on physical action, and in turn, body weight. Conversely, researchers have looked at whether living in communities that "sprawl" -those with pedestrian-unfriendly streets, spread-out populations, and larger distances between homes and business areas-makes people more likely to drive rather than walk or bicycle for transportation or leisure. Some studies have plant that living in more walkable neighborhoods, or in communities with less sprawl, is linked to higher rates of physical action (i,36,37) and lower body mass index (BMI) levels (38–40). However, some studies with stronger research designs don't notice a strong relationship between walkability or sprawl and physical activeness; (41) the relationship may vary past age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and other factors. (35,42)

A number of studies have looked at whether living in a "walkable" neighborhood-one that has sidewalks, crosswalks, stores, and leisure destinations-has a positive effect on physical action, and in turn, body weight. Conversely, researchers have looked at whether living in communities that "sprawl" -those with pedestrian-unfriendly streets, spread-out populations, and larger distances between homes and business areas-makes people more likely to drive rather than walk or bicycle for transportation or leisure. Some studies have plant that living in more walkable neighborhoods, or in communities with less sprawl, is linked to higher rates of physical action (i,36,37) and lower body mass index (BMI) levels (38–40). However, some studies with stronger research designs don't notice a strong relationship between walkability or sprawl and physical activeness; (41) the relationship may vary past age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and other factors. (35,42)

Neighborhood Safety and Social Cohesion

Risks to safety tin run the gamut from reckless drivers and "stranger danger" to bullies in the playground. (44) And there's evidence that if people believe their neighborhoods are unsafe, children are less likely to play outside, and adults are more than wary nearly walking or taking office in other physical activities. (4,45,46) A recent study found that Los Angeles residents who perceived their neighborhoods as dangerous had significantly college BMIs than those who considered their communities safe. (47)

Studies that used objective measures of neighborhood criminal offence accept establish that higher levels reduce walking or concrete action, especially amidst women and young children. (48–50) Conversely, those who alive in areas with more trust or "social cohesion" tend to have higher levels of physical activity. (51,52)

Policies That Shape Our Physical Activity Environment

Policy is a powerful tool for shaping our environments and lifestyles. Public health researchers are particularly interested in identifying how policy changes and big-calibration investments in transportation infrastructure can increase physical activity. (53,54)

Land-Use Policies

In the U.Southward., federal housing loans and straight subsidies for highway development are two major policy decisions that fueled the rise of sprawling suburban developments during the last half of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st century. (55) Combined with rapid advances in automotive applied science and increased manufacturing capacity, they launched an exodus from the inner cities to the suburbs and changed the residential mural. Nonetheless, local cities and towns tin enact land-utilise policies, such as zoning regulations and building codes, to create customs-broad environments that support physical activity. (54) At that place's evidence that "mixed land apply"-locating residential areas well-nigh shops, schools, offices, and other destinations, rather than spread autonomously-is related to walking and physical activeness levels. (1,35,56)

Access to Public Transportation

Walking to and from public transportation may assistance sedentary individuals, particularly from depression-income and minority groups, meet recommended levels of daily concrete activity. (57) Indeed, an estimated 90 per centum of public transit trips in the U.South. involve walking at the outset or end of the trip. (58) While walking is associated with lower take a chance of obesity, there's show that motorcar travel has the opposite event: Frank and colleagues found that each additional hour per day spent in a car was associated with a 6 pct increment in the likelihood of obesity. (59) That'due south why the Centers for Disease Command and Prevention recommends that communities improve access to public transportation as an obesity prevention strategy, since better access to public transportation may encourage people to employ information technology. (60)

Cycle and Pedestrian-Friendly Street Designs and Policies

Bike Runway, New York City

Travel behavior trends in the U.S. could hardly be worse for public health: Recent data finds that U.S. children and adults use bicycles for just i percent of all trips. (58) In kingdom of the netherlands, by contrast, 27 pct of trips are made past bicycle. (61) While people in the U.Southward. are making more trips by walking-10.five percent of all trips in 2009, up from eight.6 percent in 2001-only about 18 per centum walk for transportation, a number that hasn't budged in the past decade. (58)

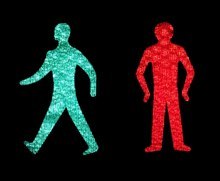

Based on successful support of active transport in Europe, a number of policy options have been proposed. Some focus on making streets safer for walking and biking: Reduced speed limits, longer pedestrian crossing times, wider sidewalks, the use of traffic-calming devices (such as plantings) in roadways, auto-free city zones, and protected, defended bicycle lanes are a few approaches. (ii,62,63) Other options include offer incentives for leaving the car at home, or making it easier to walk or wheel to public transit. London, for example, made comprehensive wheel path, bike parking, and traffic prophylactic improvements in the early 2000s, and congestion pricing-where drivers are charged a fee to enter the metropolis-in 2003. These changes have been accompanied by a doubling in bicycle trips and a 12 percent reduction in serious cycling injuries from 2000 to 2008. (64)

In the U.Southward., the National Complete Streets Coalition advocates for a comprehensive list of policies that local, land, and federal governments can use to make streets safer for drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians. (65) One area of controversy is related to different views on the safest mode to accommodate bicycling. Cycle tracks-barrier-protected, bicycle-only travel lanes located next to sidewalks-are one approach used in the Netherlands, which has much lower rates of cycle injuries than the U.S. Cycle tracks are less mutual in North America, where transportation guidelines favor cycling on striped bike lanes in the street. A recent written report in Montreal, however, finds that biking in cycle tracks is safer than biking on the street. (66)

The Bottom Line: Edifice an Environment that Supports Active Lifestyles

Our surroundings and the policies that shape them accept a substantial affect on where, when, how, and how much concrete activeness we go on a daily basis. Merely as our lack of concrete activeness is a major correspondent to the obesity epidemic, creating an activity-friendly environs is one way to assistance turn effectually the epidemic. There are many elements to an activity-friendly environs: buildings, streets, and communities that encourage walking and biking; parks and playgrounds that are plentiful and highly-seasoned; and neighborhoods where people experience-and are-safe, to proper name a few. How can communities brainstorm the job of creating spaces and places that promote activity? They tin beginning past considering the health touch of development and transportation projects, much the same fashion they consider the environmental affect of these projects. (67) Such changes will be essential to attain the goal of making physical action a regular and natural part of people's daily lives.

References

1. Ding D, Sallis JF, Kerr J, Lee Due south, Rosenberg DE. Neighborhood environment and physical activeness amidst youth, a review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:442-55.

ii. Pucher J, Buehler R, Seinen M. Bicycling renaissance in N America? An update and re-appraisal of cycling trends and policies. Transportation Research Role A: Policy and Practice. 2011; 45:451–475

3. Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen Air conditioning. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:129-43.

four. Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:7-20.

5. Sallis JF, Glanz One thousand. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87:123-54.

6. Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Burgeson CR, Fisher MC, Ness RB. Translating epidemiology into policy to prevent childhood obesity: the case for promoting physical activity in schoolhouse settings. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;xx:436-44.

7. Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Donatelle RJ, King AC, Brown D, Sallis JF. Physical action social support and middle- and older-aged minority women: results from a US survey. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:781-nine.

8. Ferreira I, van der Horst K, Wendel-Vos W, Kremers Southward, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth—a review and update. Obes Rev. 2007;8:129-54.

ix. Beets MW, Cardinal BJ, Alderman BL. Parental social support and the physical activity-related behaviors of youth: a review. Wellness Educ Behav. 2010;37:621-44.

10. Cleland V, Timperio A, Salmon J, Hume C, Telford A, Crawford D. A longitudinal report of the family physical activity environs and physical activity among youth. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25:159-67.

11. van Sluijs EM, Kriemler S, McMinn AM. The event of community and family interventions on young people'south physical activity levels: a review of reviews and updated systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:914-22.

12. O'Connor TM, Jago R, Baranowski T. Engaging parents to increase youth physical activity a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:141-9.

13. Schulte PA, Wagner GR, Ostry A, et al. Work, obesity, and occupational safety and health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:428-36.

xiv. Katz DL, O'Connell Chiliad, Yeh MC, et al. Public health strategies for preventing and controlling overweight and obesity in school and worksite settings: a report on recommendations of the Job Forcefulness on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:i-12.

15. Atkinson G, Fullick South, Grindey C, Maclaren D. Do, energy balance and the shift worker. Sports Med. 2008;38:671-85.

16. Zhao I, Bogossian F, Song S, Turner C. The Clan Between Shift Piece of work and Unhealthy Weight: A Cross-Sectional Analysis From the Nurses and Midwives' e-Cohort Report. J Occup Environ Med. 2011.

17. Meyer P, Kayser B, Kossovsky MP, et al. Stairs instead of elevators at workplace: cardioprotective furnishings of a pragmatic intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:569-75.

18. Nicoll G, Zimring C. Effect of innovative building design on physical activity. J Public Health Policy. 2009;thirty Suppl 1:S111-23.

xix. Soler RE, Leeks KD, Buchanan LR, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Hopkins DH. Point-of-decision prompts to increase stair apply. A systematic review update. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S292-300.

20. Herman CW, Musich S, Lu C, Sill S, Young JM, Edington DW. Effectiveness of an incentive-based online physical activeness intervention on employee health status. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:889-95.

21. Anderson LM, Quinn TA, Glanz Grand, et al. The effectiveness of worksite diet and concrete action interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:340-57.

22. Barr-Anderson DJ, AuYoung One thousand, Whitt-Glover MC, Glenn BA, Yancey AK. Integration of brusk bouts of physical activity into organizational routine, a systematic review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:76-93.

23. Lachapelle U, Frank LD. Transit and health: mode of transport, employer-sponsored public transit laissez passer programs, and physical activeness. J Public Wellness Policy. 2009;30 Suppl 1:S73-94.

24. Kaczynski AT, Bopp MJ, Wittman P. Clan of workplace supports with active commuting. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;seven:A127.

25. Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD001871.

26. Katz DL, O'Connell M, Njike VY, Yeh MC, Nawaz H. Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: systematic review and meta-assay. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1780-nine.

27. Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, Watkins LT, Johnson CC, Webber LS. Safe play spaces to promote physical action in inner-city children: results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1625-31.

28. McDonald NC, Brown AL, Marchetti LM, Pedroso MS. U.S. schoolhouse travel, 2009 an assessment of trends. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:146-51.

29. Lubans DR, Boreham CA, Kelly P, Foster CE. The relationship between agile travel to school and wellness-related fitness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:five.

xxx. Mendoza JA, Watson 1000, Nguyen N, Cerin E, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA. Active commuting to school and association with concrete activity and adiposity among Usa youth. J Phys Act Health. 2011;eight:488-95.

31. Ding D, Gebel Thousand. Built environment, concrete activity, and obesity: What have we learned from reviewing the literature? Health Place. 2011.

32. Hannon C, Cradock A, Gortmaker SL, et al. Play Across Boston: a community initiative to reduce disparities in admission to afterwards-schoolhouse physical activity programs for inner-city youths. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;iii:A100.

33. Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, Brines SJ. Availability of recreational resource in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:16-22.

34. Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Harper D. Availability of physical activeness-related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1676-80.

35. Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The built environs and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic prove. Health Place. 2010;xvi:175-ninety.

36. Frank LD, Schmid TL, Sallis JF, Chapman J, Saelens BE. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: findings from SMARTRAQ. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:117-25.

37. Berke EM, Koepsell TD, Moudon AV, Hoskins RE, Larson EB. Association of the congenital environment with concrete activity and obesity in older persons. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:486-92.

38. Ewing R, Schmid T, Killingsworth R, Zlot A, Raudenbush S. Human relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity. Am J Wellness Promot. 2003;18:47-57.

39. Li F, Harmer P, Cardinal BJ, et al. Built surround and 1-year alter in weight and waist circumference in heart-aged and older adults: Portland Neighborhood Environment and Wellness Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:401-eight.

forty. Rundle A, Roux AV, Free LM, Miller D, Neckerman KM, Weiss CC. The urban congenital surround and obesity in New York Urban center: a multilevel analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21:326-34.

41. Lee IM, Ewing R, Sesso Hard disk drive. The built surround and concrete activity levels: the Harvard Alumni Health Written report. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:293-viii.

42. Dunton GF, Kaplan J, Wolch J, Jerrett K, Reynolds KD. Concrete environmental correlates of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2009;ten:393-402.

43. Stark Casagrande S, Gittelsohn J, Zonderman AB, Evans MK, Gary-Webb TL. Association of walkability with obesity in Baltimore City, Maryland. Am J Public Health. 2010.

44. Carver A, Timperio A, Crawford D. Playing it prophylactic: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children'south physical action. A review. Health Identify. 2008;xiv:217-27.

45. Harrison RA, Gemmell I, Heller RF. The population effect of crime and neighbourhood on physical activity: an analysis of 15,461 adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:34-9.

46. Molnar BE, Gortmaker SL, Bull FC, Buka SL. Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of condom predict reduced physical activeness amidst urban children and adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2004;eighteen:378-86.

47. Fish JS, Ettner S, Ang A, Brown AF. Clan of perceived neighborhood prophylactic on trunk mass index. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2296-303.

48. Gomez JE, Johnson BA, Selva K, Sallis JF. Violent law-breaking and outdoor physical activity among inner-city youth. Prev Med. 2004;39:876-81.

49. Brownish HS, 3rd, Perez A, Mirchandani GG, Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH. Offense rates and sedentary behavior amongst 4th grade Texas school children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Deed. 2008;5:28.

50. Bennett GG, McNeill LH, Wolin KY, Duncan DT, Puleo E, Emmons KM. Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1599-606; discussion 607.

51. Cradock AL, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Gortmaker SL, Buka SL. Neighborhood social cohesion and youth participation in physical activity in Chicago. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:427-35.

52. Lindstrom M, Hanson BS, Ostergren PO. Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: the role of social participation and social majuscule in shaping wellness related behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:441-51.

53. Saelens Be, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:80-91.

54. Heath GW, Brownson RC, Kruger J, Miles R, Powell KE, Ramsey LT. The effectiveness of urban design and land utilise and transport policies and practicies to increment physical actvity: a systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2006;3:S55-S76.

55. Hayden D. Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000. New York: Pantheon; 2003.

56. Durand CP, Andalib Thousand, Dunton GF, Wolch J, Pentz MA. A systematic review of built environment factors related to physical activeness and obesity risk: implications for smart growth urban planning. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e173-82.

57. Besser LM, Dannenberg AL. Walking to public transit: steps to help see physical activity recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:273-fourscore.

58. Pucher J, Buehler R, Merom D, Bauman A. Walking and cycling in the United States, 2001-2009: show from the National Household Travel Surveys. Am J Public Health. 2011;101 Suppl one:S310-vii.

59. Frank LD, Andresen MA, Schmid TL. Obesity relationships with community blueprint, physical activity, and fourth dimension spent in cars. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:87-96.

60. Khan LK, Sobush Thousand, Keener D, et al. Recommended customs strategies and measurements to foreclose obesity in the Usa. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:i-26.

61. Maibach Eastward, Steg L, Anable J. Promoting physical action and reducing climatic change: opportunities to supplant short car trips with agile transportation. Prev Med. 2009;49:326-7.

62. Woodcock J, Banister D, Edwards P, Prentice AM, Roberts I. Energy and transport. Lancet. 2007;370:1078-88.

63. Pucher J, Dijkstra Fifty. Promoting condom walking and cycling to improve public wellness: lessons from The Netherlands and Frg. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1509-sixteen.

64. Pucher J, Dill J, Handy S. Infrastructure, programs, and policies to increase bicycling: an international review. Prev Med. 2010;fifty Suppl 1:S106-25.

65. National Complete Streets Coalition. Consummate Streets. Accessed January thirty, 2012.

66. Lusk AC, Furth PG, Morency P, Miranda-Moreno LF, Willett WC, Dennerlein JT. Chance of injury for bicycling on cycle tracks versus in the street. Inj Prev. 2011;17:131-5.

67. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Touch on Assessment. Accessed Jan 30, 2012.

Source: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-causes/physical-activity-environment/

0 Response to "Peer Reviewed Studies on the Association of Income With Obesity and Physical Fitness"

Postar um comentário